(c0ntinued from part two)

Life in Mashpee and Cotuit in the early 19th century was dominated by the fast growth of the Nantucket whaling fishery. Cranberries had not yet been cultivated commercially, transportation on and off the Cape was either by horse and wagon but mainly by ship, and there was little to no tourism in the modern sense of the word. The US Senator from Massachusetts, Daniel Webster, was fond of fishing in Mashpee for sea-run brown trout, and may have lodged in the inn located in Santuit on the eastern banks of the Santuit River, the site of the present Cahoon museum. Other dignitaries, such as Yale’s Timothy Dwight and Ezra Stiles, paid calls on the Reverend Gideon Hawley, the missionary to Mashpee and a graduate of that college’s seminary who also made his home near the major intersection of modern day Routes 28 and 130. The economic life of the region was mostly agricultural and based on either fishing and shellfishing, farming such as could be encouraged from the sandy soil, some livestock, and the supply of manpower for the whaling fishery.

Wampanoag men were very active in the Nantucket whaling fleet and readers may recall that one harpooner of the Pequod, Tashtego, was a Wampanoag from the praying town of Aquinnah on Martha’s Vineyard. The whaling fishery made a number of Quaker merchants very wealthy men, and for a time Nantucket was one of the most wealthy places on the planet, if not certainly the most international, its crews opening up the South Pacific in the early 19th century for the first time since the voyages of discovery by Cook. Whaling was an extremely dangerous profession and life on the greasy, slow, smoke-belching ships was neither easy nor especially lucrative for ordinary seamen. Some historians say Wampanoag employment in the whaling industry had a terrible effect of attrition on the male population. Those Wampanoag males that remained ashore practiced a subsistence lifestyle based on the traditional agricultural staples of corn, beans and squash, hunting and fishing.

In 1833 Mashpee was still governed by the board of overseers appointed by the Governor and the Trustees of the Williams Fund of Harvard which furnished a minister and funds for his support as well as the maintenance of the old Indian Meetinghouse. An Indian pastor hadn’t ministered to a flock in the meeting house for decades, and by the time the Rev. Gideon Hawley ended his tenure, the Wampanoags had started to drift away from Congregationalism to the Baptists and Methodists, the former led by the Rev. “Blind” Joe Amos, a Wampanoag. In 1809 Harvard appointed one its own, the Reverend Phineas Fish, to be the official missionary and Congregationalist Minister of Mashpee. Fish was paid an annual salary of $520, a $350 “settlement fee” and granted “as much meadow and pasture land, as shall be necessary to winter and summer.” The historian Donald Nielsen, in his essay “The Mashpee Indian Revolt of 1833″ wrote: “The sale of wood from the parsonage woodlot brought him [Fish] several hundred dollars more per year. Fish was assured a comfortable living on Mashpee land with money designated to help the Indians, yet he was in no way accountable to his flock.”

That lack of accountability, and what emerges through time as a somewhat churlish personality, was the undoing on Phineas Fish and the spark of the Woodlot Revolt. The tinder was supplied by William Apess, a fascinating figure who may stand as the earliest and most eloquent native American writer and activist concerned with native sovereign rights.

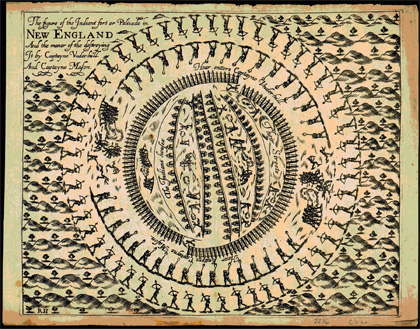

Apess was born in Colrain, Massachusetts near the Vermont border in 1798 of mixed-ancestry, a so-called “half-breed” who’s father may have been African American, but who’s mother was full-blooded Pequot Indian originally from southeastern Connecticut. The Pequots were the victims of the first English massacre, one that took place in Mystic, Connecticut in 1637 when a colonial militia surrounded a Pequot fort and killed 400 to 700 women, children and elderly (the able-bodied men were outside of the palisade scouting for the English force and thus spared until later hunted down and killed.)

I digress back two centuries to the first massacre of Indians on American soil only to lay the foundations for Apess’ subsequent activism as a voice for Indian rights. He was raised in terrible conditions, severely beaten by his grandmother at the age of four, raised as an unruly delinquent, raised as a foster child by white parents who despaired of his lying and thievery — traits he freely admits himself in his autobiography, A Native of the Forest. He enlisted in a New York state militia regiment bound for the Canadian front during the War of 1812 and became the object of much teasing by older soldiers in his regiment who amused themselves by giving Apess liquor and encouraging his drunkenness. Following the War, Apess lived an itinerant existence throughout southern New England working as a cook and a laborer, eventually falling in love with a Pequot girl also of mixed-race, who reformed his ways and helped him sober up and continue his limited education. She gave birth, a family was started and in 1815 Apess was ordained as a Methodist minister. The historian Barry O’Connell at the University of Massachusetts wrote: “William Apess was a nobody. Born into poverty in 1798 in a tent in the woods of Colrain, Massachusetts, his parents of mixed Indian, white, and possibly African American blood, this babe had attached to him nearly every category that defined worthlessness in the United States.”

The Methodist tradition is one of the itinerant preacher who goes on the road to preach the word of God to whatever willing flock he can find along the way. Apess wrote and self-published A Son of the Forest, the first autobiography by an American Indian, and became increasingly focused on Indian rights and injustices.

In the spring of 1833 Apess, hearing about the thriving Wampanoag community in Mashpee, wrote to the Reverend Fish asking for an opportunity to visit and preach to his fellow Indians. Fish extended an invitation and Apess made his way to Cape Cod.

When Apess took the pulpit at the Old Indian Meetinghouse and began his sermon he became indignant as the lack of any native faces. The congregation was almost entirely white, comprised of worshippers from Cotuit and Santuit for the most part. Apess wrote:

“I turned to meet my Indian brethren and give them the hand of friendship; but I was greatly disappointed in the appearance of those who advanced. All the Indians I had ever seen were of a reddish color, sometimes approaching a yellow, but now, look to what quarter I would, most of those who were coming were pale faces, and, in my disappointment, it seemed to me that the hue of death sat upon their countenances. It seemed very strange to me that my brethren should have changed their natural color and become in every respect like white men.”

Apess finished his sermon, thanked the Reverend and immediately sought out the leaders of the tribe to seek an explanation for why their most cherished building, their church, had been taken over by the whites. The leaders of the Wampanoags, led by the popular Reverend Blind Joe Amos gathered, expressed their grievances with the white-imposed system of oversight, the utter lack of any relationship to the Reverend Fish, and a litany of grievances around white incursions onto Mashpee lands. Apess. obviously a man of words accustomed to persuasion with his tongue, was also a born leader, and he emerged from those first meetings with the tribe as an “adopted” son of Mashpee, granted the trust and authority to represent the Wampanoags in their future dealings with the whites.

As a bit of historical context, 1833 was a time of profound foment in American politics that saw a great deal of chafing between the southern states and the Federal government, a friction that would, three decades later, lead to the War Between the States. In South Carolina, the hotbed of American secessionism, the US Senator John C. Calhoun had led a bitter fight against Federal tariffs under the auspices of “nullication“ a long-standing point of Constitutional law that defined the rights of the states to reject or “nullify” Federal legislation and mandates. Apess seized on the contemporary awareness of nullification and applied it to the situation in Mashpee, drafting a manifesto and statement of grievances that in essence said Mashpee was a sovereign nation established by the land grants of Richard Bourne and was in no way subject to the laws and oversight of any government body other than its own. E.g. Mashpee was not subject to the laws of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

A petition was drafted and presented to the legislature in Boston. Among its resolutions:

“Resolved: That we as a tribe will rule ourselves, and have the right so to do for all men are born free and Equal says the Constitution of the County.

“Resolved: That we will not permit any white man to come upon our plantation to cut or carry of [sic] wood or hay any other artickle with out our permission after the first of July next.

“Resolved: That we will put said resolutions in force after that date July next with the penalty of binding and throwing them from the plantation If they will not stay a way with out.”

A second petition was filed with Harvard calling for the removal of the Reverend Phineas Fish.

The reaction of the legislature was somewhat benign, but locally, one can imagine the reaction of the whites in Barnstable, Sandwich and Falmouth to the Wampanoag declaration of independence and the setting of a deadline of July 1, 1833 for all whites to evacuate Mashpee. In the Barnstable Patriot, the editor, one Sylvanus Bourne Phinney wrote that Apess had been distributing his pamphlet: “Experiences of Five Christian Indians of the Pequot Tribe” and stirring up some ugly emotions: “The teachings of this man are calculated to excite the distrust and jealousy of the inhabitants towards their present guardians and minister and with his pretensions to elevate them to what we all wish they might be, he will make them, in their present ill-prepared state for such preaching, ten times more turbulent, uncomfortable, unmanageable and unhappy than they are now.”

After the Wampanoag delegation led by Apess filed their petitions on Beacon Hill in June, 1833, they returned to the Cape “mistakenly supposing Governor Levi Lincoln approved of their reforms.” In fact, other than the local whites in the towns surrounding Mashpee, and the Reverend Phineas Fish, no one appeared to take the Wampanoags seriously.

Later that month the tribe notified the treasurer of the Board of Overseers, Obed Goodspeed, to turnover the plantation’s books and other papers. A tribal council was formally elected on June 25 and public notices were printed and displayed so that “said Resolutions be inforced.” On June 26, Reverend Fish was told “be on the Lookout for another home. We of no Indian that has been converted under your preaching and from 8 to 12 only have been your Constant Attenders. We are for peace rather than any thing else but we are satisfied we shall never enjoy it until we have our rights.”

This got the Reverend Fish’s attention. In panic at the unrest around him, the priggish clergyman wrote a letter to Governor Lincoln and had his predecessor’s son, Gideon Hawley, Jr., deliver it on horseback to Lincoln at the governor’s home in Worcester. Apess wrote afterwards that Fish wrote: “…the Indians were in open rebellion and that blood was likely to be shed .. It was reported and believed among us that he said we had armed ourselves and were prepared to carry all before us with tomahawk and scalping knife; that death and destruction, and all the horrors of a savage war, were impending; that of the white inhabitants some were already dead and the rest dreadfull alarmed! An awful picture indeed.”

The deadline of July 1 was only a few days away.

(to be continued).