One of my earliest memories is from the age of two or three, riding in the back seat of an old Plymouth being driven at night by my father, my mother beside him, along some Greater Boston parkway, probably on our way to Melrose to see my grandparents. No kiddie seat. No seatbelt. Just me alone in the backseat, unattended and laying on my back, looking up through the rear window at the street lights flashing past in a hypnotic green pattern.

Street lights cast a green splash of light then. Bare incandesent bulbs suspended under a scalloped metal reflector hung over the streets, probably the 1.0 or 2.0 version of electric street lights, the first generation to be installed after they did away with horses and buggies and gaslights. I’ve always missed that greenish hue, though lord knows my brother and I did our best with our delinquent friends blasting out the bulbs with our WristRockets and pockets full of ball bearings salvaged from an old Pachinko machine we got one Christmas.

At some point the street lights of my childhood were all converted to orange high pressure sodium vapor lamps — salmon colored light that made everything flat and ugly. I hated them when they appeared in the 1970s. As one fellow sodium vapor hater, Hal Espen, wrote in the Atlantic Monthly in 2011:

“Following the economic imperative to use the most cost-effective lighting—high-pressure sodium lights consume half as much energy as mercury-vapor lamps and can last up to 16,000 hours longer—transportation departments and cities embraced sodium light. It was as though someone said “Fiat lux sulfurea—“Let there be light from hell.” The relentless spread of sodium streetlights is documented in NASA night photographs from space: New York City and Los Angeles are circuit boards of glowing orange, and Long Beach, one of the world’s busiest ports, is a flare of tarnished gold. It’s even worse in the United Kingdom, where 85 percent of streetlights use sodium. The jaundiced weirdness of sodium light has become a vexing challenge to photographers (one filmmaker, Tenolian Bell, called it “the ugliest light known to the cinematographer”); movie cameras simulate its color by using a gel filter named Bastard Amber.”

I never realized how much I hated them until one night in late November in 1980 when I was delivering an elderly 60′ plywood catamaran named the Dushka from Falmouth to West Palm Beach and entered Chesapeake Bay in bad weather. I had never been that far south and we made landfall on our second night out of Falmouth — a sleepless 48 hour stretch because I was the only person on board who could navigate let alone sail the demonic craft which sailed so fast it left the tops of the ocean swells and went airborne from time to time with terrifying results.

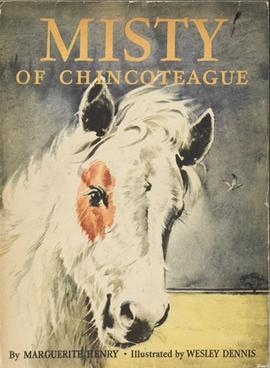

As we coasted down the Delaware and Virginia coast that afternoon I had a very good idea of where we were. I was dead reckoning — essentially estimating our position by keeping close track of distance, speed and time — and cross checking that with the depth finder and an semi-useless radio directional finder. As we screamed along at 15 knots, past the Chincoteague Island (home of the wild horses, where the children’s book Misty of Chincoteague was set)  I was very aware of the failing light and the unfortunate timing of our landfall with the Chesapeake. I thought about standing offshore for the night and coming in the next morning, but the NOAA radio was talking up a gale and I was really looking forward to some sleep. As we blasted along the shoreline, about two miles out, I said goodbye to the setting sun and stared at the orange street lights popping on one after another, all the while imagining the boardwalks and shuttered amusement parks underneath them in places like Rehoboth Beach and Ocean City, Maryland. And then I thought about the lucky people in their warm houses watching television after they finished a real meal, not one cooked by a seasick person who destroyed a pot of American Chop Suey by vomiting in it because he couldn’t unclip himself from the gimballed stove in time to make it on deck and the leeward rail (which was probably for the best given that American Chop Suey has so much wrong with it in both theory and practice).

I was very aware of the failing light and the unfortunate timing of our landfall with the Chesapeake. I thought about standing offshore for the night and coming in the next morning, but the NOAA radio was talking up a gale and I was really looking forward to some sleep. As we blasted along the shoreline, about two miles out, I said goodbye to the setting sun and stared at the orange street lights popping on one after another, all the while imagining the boardwalks and shuttered amusement parks underneath them in places like Rehoboth Beach and Ocean City, Maryland. And then I thought about the lucky people in their warm houses watching television after they finished a real meal, not one cooked by a seasick person who destroyed a pot of American Chop Suey by vomiting in it because he couldn’t unclip himself from the gimballed stove in time to make it on deck and the leeward rail (which was probably for the best given that American Chop Suey has so much wrong with it in both theory and practice).

Anyway, pardon the sailory digression, but things got very confusing as we tacked off of Virginia Beach and Cape Henry to make our run down the shipping channel into the Bay. Two things confused me in the darkness. First was the mental image I had of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge and Tunnel. I pictured either a bridge OR a tunnel but not both. There was this really long string of orange sodium street lights marking the bridge. I got that part. But then there were none. Where did one steer? Was there a high span to the bridge that one crossed under? For some reason I was confused by the concept of a bridge that suddenly turned into a tunnel for a short stretch, but that was indeed the situation. So I aimed for the dark spot in the span — where the lights ended — and trusted that we wouldn’t meet our deaths when I drove the miserable multihull into a dark abutment at full speed.

(this is why it is better to sail into strange places during the day)

(this is why it is better to sail into strange places during the day)

Compounding my confusion was the presence of a LOT of random orange street lights in front of the bridge, really weird clumps of them. Those turned out to be big ships riding out the night at anchor. Container ships, freighters, tankers, etc.. A whole flotilla of them moored in the open ocean. I didn’t know ships did that. I thought they made straight away for the big ship equivalent of a marina, but no, turns out big ships will wait outside of a port the way semi-trailers park in rest areas on Route 95. Makes sense. You don’t want to haul a load of toilet paper into downtown Manhattan at three a.m. when there is no one around to unload it and no place to park until there is. You pull off into the Thomas Edison Rest Area and take a nap.

As we drew closer to the entrance and passed a couple of the moored ships all lit up with their street lights, I figured out the phenomenon of big boats anchored out in the big ocean but still had to trust the navigational chart and fight my innate instincts. I had to trust that the black gap in the bridge lights was indeed where one entered the Bay. It was. We shot through the gap and were safe inside, the angry Atlantic behind us. At which point the storm hit and began to rain buckets. I had no idea of where we were going other than the plan was to use the Intercoastal Waterway from Norfolk, Virginia south to Morehead City, North Carolina to avoid the Graveyard of the Atlantic, aka Cape Hatteras. I gave the wheel to the one person I trusted the most to steer the boat, popped down below, and studied the chart for the nearest possible place to anchor and ride out the storm. There was a very nice little harbor right inside of the bridge called Little Creek. The chart showed docks, just like a marina’s slips. I thought just maybe there would be a restaurant still open. With a bar.

The crew of the good ship were very happy by my decision to seek the nearest port in the storm. We doused the sails, fired up the engine and motored right into Little Creek. It was 3 AM. The place was quiet. I used a big flash light to pick our way down the channel. I guess the “Warning: Keep Out” sign should have been sufficient warning, but it was really howling and raining so I held my course. We passed through the breakwaters and into the middle of a big industrial boat basin lined with immense grey naval ships. Uh oh. Turns out the full name of Little Creek is the US Navy’s Joint Expeditionary Base/Little Creek-Fort Story, the largest amphibious warfare base in the world. I motored around the perimeter of the world’s most powerful navy’s collection of amphibious assault craft looking for a place to tie up to the dock, but it was wall-t0-wall with ships and then some more ships. Big ominous war ships all lit up with big orange streetlights. So I decided to anchor in the middle of Little Creek, as far away from the warships as I could get; lit the Dushka’s dim little masthead and anchor lights, and hit the rack for some sleep. And I slept. For about two hours. Then the bullhorns and sirens started.

“ATTENTION. ATTENTION. THIS IS THE UNITED STATES COAST GUARD.”

That is a very effective alarm clock. I climbed on deck wearing only boxer shorts. There was a Coast Guard 44-foot patrol boat beside us, covered with serious Coast Guardsmen holding serious guns. The rest of our motley crew came on deck and gawked.

I waved like an idiot. “Heyhowareya?” I asked. Playing dumb because I was. The Coast Guard came aboard, looked at the boat’s documents, asked some polite questions, and basically agreed with my statement of the obvious that the weather the night before had been really shitty and what was a 21 year-old knucklehead to do at three a.m.?

Last night, as I drove home after a week away, I realized that forty years of stark nacreous orange light in front of my house on Cotuit’s Main Street had been replaced by something new, something sharp, something clear and almost green-like (but more blue-like in truth). After years of a malfunctioning light that lit up, triggered the photo sensor into believing it was daylight, and then switched off again — over-and-over-and-over — the Prudential Committee of the Cotuit Fire District (or some other higher municipal power) has replaced the street lights with really bright modern LEDs.

Apologies for the blurry cell-phone picture, but you can see the old sodium lights to the left over the hill by the former Cotuit Inn and the new LEDs of which I blog in the foreground. I guess I’m easily pleased, especially in depths of a Cape Cod February when the biggest action in town is when the harbor manages to freeze over. According to the Barnstable Patriot, LEDs save a ton of money and are being phased in across the Cape.

Death to sodium vapor lighting.

Once again remarkably graceful and insightful writing; exciting, too. Thank you David.

Great story……. That said, at the risk of sounding somewhat jealous (we’re actually VERY jealous), those of us in the Cotuit boonies think your new lights are glitzy and showy.

hey, happened upon your blog and read the post. i’m 22 now, and i prefer the older streetlights as well. however, here in the south, the old mercury vapour bulbs (the greenish ones you’re describing— incandescents were used before those) weren’t replaced en masse until the early/mid 90s, so we had them for a lot longer. in addition, it’s not terribly difficult to find towns that still are heavily lit by mercury vapour lights— one example is greenville, south carolina:

http://www.greenvilledailyphoto.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/09/20090922_rain_900x600.jpg

another is montgomery alabama, which has mercury vapour lights only on the residential streets.

my biggest problem with the sodium streetlights is that they are so anti-night. it’s like permanent sunset, and here in the atlanta area (close to 6 million people), you can be 100 miles off from the city and you see this weird brown glow over the horizon. by the time you get in the city, the entire sky has this orange/brown glow and it is impossible to see the stars. i’m hoping atlanta is next for the LED street lights, simply because it’s like having night time back again. of course, i’d love to have the mercury street lights back, but that ain’t never gonna happen.